What you need to know about truth-telling

Frequently asked questions about truth-telling processes and our approach

Beyond contexts of immediate aftermath of large-scale violations, transitional justice is increasingly used to redress legacies of human rights abuses through judicial and non-judicial measures such as criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations programs, and various kinds of institutional reforms. Meanwhile, Restorative Justice is a forward-looking approach. It acknowledges that repair can be done when acknowledging the relationship between victim, offender and community caused by harm. It offers opportunities to create new collective futures by a victim-centered approach. Then, there is a more expansive approach to restorative justice which is Transformative Justice. Transformative Justice is the idea that justice will only occur if there is a fundamental restructuring of social, political, and cultural relationships within societies in order to dismantle systems of oppression and prevent future oppression. We argue that there is an interplay between these three concepts of justice, with a common focus on addressing exclusionary and discriminatory hierarchies of power that drive societal division by focusing on revisiting the social contract as one based in creating more inclusive institutions, the rule of law grounded in human rights, and a pluralistic narrative in which all residents are an equal part of society.

Transitional justice normally refers to a nation state that emerges from a period of conflict and repression and addresses large-scale or systematic human right violations that are so grave that the normal justice system isn’t able to provide the response that is needed. However, beyond contexts of immediate aftermath of large-scale violations, transitional justice is increasingly being used to redress legacies of human rights abuses at sub-state levels. Our research posits that transitional justice principles can help us work toward a more just and equitable Los Angeles. At a nation-state level, transitional justice processes most commonly take place in the immediate aftermath of mass atrocities for which the state had primary responsibility. A city-level process is more complex in that there are potentially more actors responsible for historic harms, making accountability less clear. As well, harms will tend to be less immediate but more long-term and structural. Nonetheless, in both contexts there are common ways to effectively address past harms in ways that prevent their recurrence. This should be grounded in a process that centers recognition of historic wrongs, active responsibility-taking, and reparative processes to help heal past harms. Progress with each of these domains depends on community and city cooperation.

If we consider transitional justice to be a large scale process that is different depending on the country and the situation, we can think of restorative justice as a smaller process that can be included within the strategies of transitional justice. Transitional justice would thus be an umbrella approach where restorative is one of many initiatives beneath the overall process. So if transitional justice is a large scale human rights reimagining process within a country, restorative practices such as healing circles with victims and offenders would be facilitated as part of the attempt to reconstruct human rights situations within the country or region.

Davis and Scharrer describe this key distinction as follows. A punitive justice model asks: What law(s) were broken and by who, as well as the proper punishment for their actions. Contrasting this, a Restorative Justice model focuses on the community aspects by asking: who was harmed, the needs of every party involved, and the ways in which all parties involved can contribute to repairing the harm. Punitive justice models assume conventions in compliance with the institution of criminal justice, whereas Restorative Justice is forward-looking一dealing collectively with the aftermath of an offense and implications for the future. Recognizing that individuals exist in networks of relationships sharing a common physical, psychological, or political space, Restorative Justice views actions, individuals, and relationships in ways that offer opportunities to create new collective futures. (Davis and Scharrer, pg 98: “Reimagining and Restoring Justice”)

Retributive justice systems place the emphasis of the process on punishing the offender, whereas restorative justice practices focus on the relationship between the offender and the victim. Eduardo German Bauche explains how the construction of punitive systems are directly related to the social, cultural, economic, and political profits of the state in a given moment. The final verdict of a case in this system is not the satisfaction of the victim, but rather a successful application of a penalty that is reserved for the state (Bauché, 2018, p. 67). Restorative justice offers an alternative approach that gives more agency to the victims and tries to address the needs and voices of those involved. Through the restorative justice process the state’s needs are no longer prioritized. This is relevant to our project because we are trying to emphasize the needs of the victims of racial injustice while also trying to reduce the harmful incentives of the state in the current system that allows for this. (Germán Bauché, E., Isabel Prada, M. (2018). Diente de León: Teoría y metodología de la Justicia Restaurativa desde la práctica cotidiana. FDCJ.)

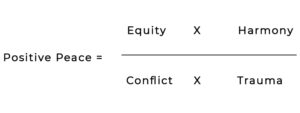

Positive Peace Theory was coined by Peace and Conflict studies expert Johan Galtung as a framework to distinguish the absence of violence and conflict, negative peace, from the “integration of human society” or positive peace. The integration of human society through positive peace depends on four fundamental variables, contingent on each other, that constitute a holistic approach to conflict resolution. This framework encompasses local government and civil society’s effort to achieve equity and build harmonious relationships with each other, while simultaneously transforming current conflicts and overcoming trauma.

Figure 1: The equation for Positive Peace set by Johan Galtung.

In Los Angeles, positive peace represents a practical guide for civil society and government actors to take responsibility for present injustices and past harms. Working towards integration, therefore, requires proactive and collaborative efforts that advance equity and harmony between residents, dismantle violent structures, and help communities and individuals heal from past traumas.

A restorative city is any municipality whose infrastructure reflects the principles of restorative justice and implements the use of restorative practices in city-level institutions, such as schools, juvenile detention centers, and youth community programs (Tchoukleva, 2020). In terms of the why, restorative cities (such as Whaganui, New Zealand, and Oakland, California) have demonstrated more success in addressing issues rooted in institutional/systemic racism than cities that have continued to solely rely on a punitive justice approach. Through the use of restorative practices (Family Conferencing, Circles, etc) at the municipal level, the city of Los Angeles can reconceptualize their approach to eliminating the school to prison pipeline, lowering crime rates, and creating equal opportunities for historically marginalized communities – Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American. Although the goals of LA as a Restorative Justice City will expand beyond just schools and the youth justice system, these arenas – which have seen the most success in the use of restorative practices – serve as a useful point of departure when considering the implementation of alternative justice practices in a city as large and diverse as Los Angeles.

Transformative Justice is a more expansive approach than either transitional justice or restorative justice. Instead of simply seeking to restore the actors, transformative justice sets out to transform individual actors and the broader society — i.e. it seeks to change the larger social structure as well as the environments, habits, thoughts, feelings of those involved (Wozniak). The bottom-line in transformative justice is that justice will only occur if there is a fundamental restructuring of social, political, and cultural relationships within societies in order to dismantle systems of oppression and prevent future oppression. Transformative justice requires multiple processes — from grassroots social mobilizations to robust institutional reform.

Kelebogile Zvobgo describes TRCs as: a “temporary body authorized by governments to investigate political violence over a period of time, and establish a pattern of violence while engaging with the affected population.” As a mechanism of transitional justice, truth commissions seek to provide an “authoritative account on the past” and “provide a framework for governments to address past harm and safeguard against future harm.” While truth commissions are often referred to as truth and reconciliation commissions or simply TRCs, not all truth commissions are specifically mandated to promote reconciliation. These commissions often conclude with a final report and a public apology that encompasses plans for non-repetition of harm, monetary or other reparations, supportive programming, etc. (Zvobgo, Truth Commissions and Transitional Justice, 7 October 2020).

Although reconciliation is a worthy goal, oftentimes truth and reconciliation commissions are unable to satisfy the victim or open a dialogue, making reconciliation difficult. In focusing on accountability, TRCs are able to simultaneously work towards three results: recognition of past harms, institution of reparative solutions, and prevention of future harms. These are especially important as they are a result of victim-centered approaches, which are essential to TRCs. Additionally, the byproduct of focusing on accountability may lead to reconciliation as a result.

Reparations were first discussed on a broad international scale in the Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC) to address grave crimes against humanity. Within the Rome Statute, reparations were broken down into five categories:

| Restitution | Restoring the victim to his/her original situation before the violation inflicted upon them. This can include but is not limited to: restoration of liberty, enjoyment of human rights, identity, family life and citizenship, return of one’s place of residence, restoration of employment, and return of property. |

| Damages Compensation | The provision of compensation “for any economically assessable damage, as appropriate and proportional to the gravity of the violation and the circumstances of each case”. Such damage includes: physical or mental harm, lost opportunities, material damages and loss of earnings, moral damage, cost of legal, medical, psychological, and social services. |

| Rehabilitation | The bestowing of medical, psychological, and psychological services in addition to legal assistance. |

| Satisfaction | Measures which include the cessation of human rights violations and abuses, truth-seeking, searches for the disappeared, recovery and reburial of remains, judicial and administrative sanctions, public apologies, commemoration, and memorialization. |

| Guarantees of non-repetition | Reforms ensuring the prevention of future abuses, including: civilian control of the military and security forces, strengthening an independent judiciary, protection of civil service and human rights workers, the overall promotion of human rights standards, and the establishment of mechanisms to prevent and monitor social conflict and conflict resolution.” https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf |

Thus, as noted in the definition we give of reparations in our “key terms” section, reparations can take many forms. As the ICTJ notes, for example, in Colombia a land restitution program was instituted that provides reparations to victims in the form of property titles, vocational training, and other economic and social goods. This is in line with the U.N.’s Pinheiro Principles on Housing and Property Restitution, which sees redistributive reparations as contributing to transformative justice.

The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) defines an institutional apology as “a formal, solemn and, in most cases, public acknowledgement that human rights violations were committed in the past, that they caused serious and often irreparable harm to victims, and that the state, group, or individual apologizing is accepting some or all of the responsibility for what happened.” (ICTJ, 2015). The responsibility avenue discusses seven aspects of an effective apology:

- Unconditional: Regardless of current government administrations the apology recognizes the institution as a whole creating and perpetuating harm.

- Shared Process: The affected community is involved in the definition of the harm and the apology is centred around what will be the most impactful for the harmed community.

- Contextualized: The apology is not used for political gain, the institutional apology is expressed in genuine terms and initiated by the community

- Accompanied by an intentional Ceremony and celebration: A ceremony or celebration of the institutional apology embeds the apology into the public memory – uniting both victims and the rest of society.

- Specific: An apology without naming the harm leaves the apology empty. Naming the harm recognizes the harm and ensures a commitment to further reparative measures.

- Include plans for future justice: Future justice outlines the institution’s plans for non-repetition of harm and removal of all harmful language, policies and structures.

- Outline plans for repetition and integration: an institutional apology is not a single event, rather the beginning of a new future in active responsibility taking. The initial apology must outline how the institution will hold itself accountable to all aspects of the apology and provide ways for the apology to be embedded in the public system.

- Unconditional: Regardless of current government administrations the apology recognizes the institution as a whole creating and perpetuating harm.

- Shared Process: The affected community is involved in the definition of the harm and the apology is centred around what will be the most impactful for the harmed community.

- Contextualized: The apology is not used for political gain, the institutional apology is expressed in genuine terms and initiated by the community

- Accompanied by an intentional Ceremony and celebration: A ceremony or celebration of the institutional apology embeds the apology into the public memory – uniting both victims and the rest of society.

- Specific: An apology without naming the harm leaves the apology empty. Naming the harm recognizes the harm and ensures a commitment to further reparative measures.

- Include plans for future justice: Future justice outlines the institution’s plans for non-repetition of harm and removal of all harmful language, policies and structures.

Outline plans for repetition and integration: an institutional apology is not a single event, rather the beginning of a new future in active responsibility taking. The initial apology must outline how the institution will hold itself accountable to all aspects of the apology and provide ways for the apology to be embedded in the public system.

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals are a benchmark for growth at the global, national, and local levels. They give a basis for working towards long-term structural change rather than the short-term fixes often prioritized in traditional development work. Work on truth and accountability — at the nation-state or sub-state (city) level — connects to SDG 16. SDG 16 provides indicators for promoting peace, justice, and strong institutions. In particular our three avenues focus on using restorative justice to build trust and cooperation between the community and city institutions. The key benchmarks to keep in mind are 16.6, 16.7, and 16.10. SDG 16.6 highlights the goal to “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels” (United Nations). In our work, this is reflected in the recognition avenue’s work in the process of identifying harms and manifesting that accountability through art and memorialization. SDG 16.6 also comes into play with the City’s need to take active responsibility for inequality within Los Angeles. This further connects to the repair group’s work in how governments can use reparations and public service as a route to develop more accountability. 16.6.2 specifies that the aim is to increase “Proportion of population satisfied with their last experience of public services” which can be attained through the community based routes such as truth commissions described in our work. 16.7 aims to “Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels” which connects to all three avenues’ work on restorative justice practices. Restorative justice as well as truth commissions center around the direct engagement of all members of a community in a dialogue. This process would satisfy SDG 16.7 by involving community members at all levels. Lastly, SDG 16.10 has a goal to “Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements”. This links directly to the process of truth commissions which first looks to the past to establish and community truth over past harms and seeks to make its conclusions transparent public information and works to ensure freedoms going forward.

A person can choose to identify as either a survivor or victim, the implications of each word are different and can be impacted by the type of trauma experienced by the individual. An individual who identifies as a survivor is implicitly associated with survivorship––i.e, of having faced their obstacles and to one degree or another having moved past them. An individual who identifies as a victim emphasizes that there is an existence of a perpetrator who is at fault for the trauma and harm they have experienced who might still hold power over them. This doesn’t show weakness but is a way of surviving/coping with trauma. These terms are fluid and an individual may identify more with either one as they process their trauma and begin to heal. Terms like these empower individuals to decide how they perceive themselves and how society perceives them. The victim-centered approach of restorative practices prioritizes the needs of those who have been harmed and supports them in their healing process, instead of focusing on the actions or intentions of the person, group, or institution that caused the harm.

Victim-centric approaches are imperative to the success of and efficacy of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions’ ability to provide affected communities with an avenue toward recovery; emphasizing and addressing the needs of the victims. In advocating for justice for past harms, a victim-centered ensures minimal amount of retraumatization and allows space for a meaningful path forward by having the community be centrally involved in this process. A victim-centered approach gives those afflicted a sense of dignity and provides a unique opportunity for healing, as opposed to focusing on the actions and intentions of the offenders.

Equality means the distribution of resources and/or goods and/or opportunities in equal amounts.

Equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and distributes resources/goods according to need.

Racism: Can range from face-to-face or covert actions toward a person that express individual prejudice, hate or bias based on race. That individual prejudice has a broader context of broader patterns of social discrimination based in implicit or explicity white supremacism. This can express itself in racialized violence that is directed at or disproportionately affects members of a certain racial group. In many cases this violence is carried out by or allowed to continue by the state. Restorative justice processes seek to address the manner in which individual racial violence flows out of societal racism and white supremacy.

Structural racism: A system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. It identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with “whiteness” and disadvantages associated with “color” to endure and adapt over time. Structural racism is not something that a few people or institutions choose to practice. Instead it has been a feature of the social, economic and political systems in which we all exist.

Institutional Racism: Institutional racism refers to the policies and practices within and across institutions that, intentionally or not, produce outcomes that chronically favor, or put a racial group at a disadvantage. Poignant examples of institutional racism can be found in school disciplinary policies in which students of color are punished at much higher rates that their white counterparts, in the criminal justice system, and within many employment sectors in which day-to-day operations, as well as hiring and firing practices can significantly disadvantage workers of color. (The Aspen Institute: Glossary for Understanding the Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Racial Equity Analysis)

Microaggressions: A more casual form of Racism that often takes the form of comments or remarks that play into racist tropes or stereotypes. Microaggressions usually do not come from a place of hatred and harm is not intended by these statements. However, just because harm is not intended by these statements does not mean that no harm is done. Research has shown that this kind of casual racism can often have a lasting psychological impact on the groups who experience it. So while at a first glance microaggressions may seem relatively harmless compared to more blatant forms of racism that does not mean these kinds of remarks are not problematic or harmful.

Structural racism: A system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. It identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with “whiteness” and disadvantages associated with “color” to endure and adapt over time. Structural racism is not something that a few people or institutions choose to practice. Instead it has been a feature of the social, economic and political systems in which we all exist.

Institutional Racism: Institutional racism refers to the policies and practices within and across institutions that, intentionally or not, produce outcomes that chronically favor, or put a racial group at a disadvantage. Poignant examples of institutional racism can be found in school disciplinary policies in which students of color are punished at much higher rates that their white counterparts, in the criminal justice system, and within many employment sectors in which day-to-day operations, as well as hiring and firing practices can significantly disadvantage workers of color. (The Aspen Institute: Glossary for Understanding the Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Racial Equity Analysis)

Microaggressions: A more casual form of Racism that often takes the form of comments or remarks that play into racist tropes or stereotypes. Microaggressions usually do not come from a place of hatred and harm is not intended by these statements. However, just because harm is not intended by these statements does not mean that no harm is done. Research has shown that this kind of casual racism can often have a lasting psychological impact on the groups who experience it. So while at a first glance microaggressions may seem relatively harmless compared to more blatant forms of racism that does not mean these kinds of remarks are not problematic or harmful.

The passive acts of placing and accepting blame constitute passive responsibility. The defining characteristic is that it is imposed by an outside source. For example, a teacher may deem a student responsible for hurting a classmate’s feelings, or a judge may deem someone responsible for a crime. The process of passive responsibility determines who bears responsibility and then disciplines them. For that reason, passive responsibility is most frequently seen in punitive justice processes where someone is blamed or deemed “responsible” for a certain crime and is punished accordingly. Active responsibility, on the other hand, arises from within an actor (person, group, institution) and emphasizes ongoing actions they take to repair harm, restore relationships, and prevent future harm. It is the actions to repair, restore, and prevent that associates active responsibility with restorative justice. In contrast to passive responsibility, the actor willingly takes responsibility, rather than having it imposed on them by another. The actor must ask what is to be done and the process does not end after an actor begins to take responsibility. Instead, active responsibility requires ongoing engagement with all other actors involved in the harm as a result of the actor’s desire to truly address harm. For these reasons, active responsibility taking is a critical component of truth-telling processes.

Community healing is subjective. That is to say, the steps that must be taken to truly heal a community and its members is defined by their needs following harm. There are two distinct areas from which the community’s needs arise following harm:

- From their roles as victims who experienced harm.

- From their roles as members who are committed to the welfare of their community and to creating healthy conditions within their community.

In our work we discuss specific routes communities can take toward a healing process, from art and memorialization, opportunities to tell their stories, and reparations.

Memorialization is a co-creating process that advances truth and recognition of past harms by allowing space for communities to mourn past losses and preserve or create a collective memory. Memorialization can include a vast array of art based practices that can bring life to victims’ pasts and create new immersive experiences for the public. These include permanent acts of memorialization — statues, monuments, memorials and other public buildings, commemorative names attached to streets, buildings, urban landmarks, murals, and art installations — and impermanent acts of memorialization — ceremonies, parades, festivals and rituals. Participatory art is a “genre of art that focuses on the participation of people as the central artistic medium and material” (Shefik, 2018, abstract). This form of art is particularly important for truth-telling and repair because it is co-created with a focus on the community, allowing the community to shape the art correctly with respect to their past, perspectives, and needs.

Restorative justice often manifests in the form of talking circles, in which a group of people sit in a circle to discuss a particular topic in a semi-structured format. Talking circles may be facilitated by one or two individuals, but are conducted in a horizontal manner where everyone has equal opportunity to participate, including facilitators. Talking circles often use a talking piece, which is frequently an object that has emotional value to one or more participants. The talking piece is framed as an invitation to speak for the person holding it and an invitation to listen for those not holding it. Talking circles, otherwise known as restorative circles, are only one example of what restorative justice looks like in practice. Another example is victim-offender conferencing, traditionally used in the criminal justice system, but restorative practices include any practice or mechanism that are based on restorative principles.

First, a city-community partnership is a partnership, alliance, or coalition between a city and non-governmental actors, community organizations, and/or individual citizens within the city. This partnership must include regular consultation, mutual commitment, a shared contribution to development, and care for and development of the living environment. A successful partnership sees both the public sector and the community contribute to the success of the truth-telling process through time, labor, and funds. City-community partnerships are a key part to our work because community engagement is necessary to establish a strong, safe, and inclusive foundation for all members. Building partnerships creates productive working relationships between constituents and the government that provide a more holistic perspective and approach to change-making.